[HOME]

2019-04-11

Excerpt

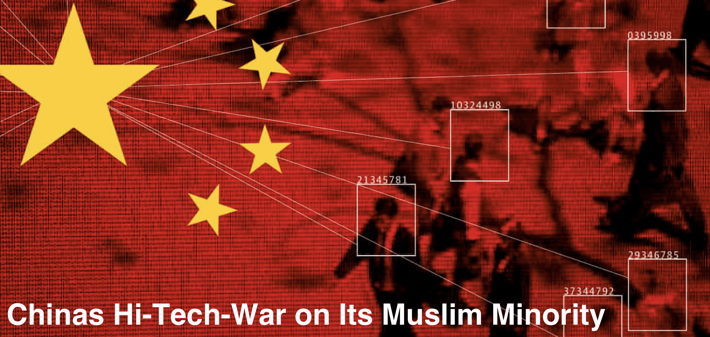

Smartphones and the internet gave the Uighurs a sense of their own identity – but now the Chinese state is using technology to strip them of it.

By Darren Byler, Thu 11 Apr 2019

The police administered what they call a “health check”, which involved collecting several types of biometric data, including DNA, blood type, fingerprints, voice recordings and face scans – a process that all adults in the Uighur autonomous region of Xinjiang, in north-west China, are expected to undergo. After his “health check”, Alim was transported to one of the hundreds of detention centres that dot north-west China. These centres have become an important part of what Xi Jinping’s government calls the “people’s war on terror”, a campaign launched in 2014, which focuses on Xinjiang. As part of this campaign, the Chinese government has come to treat almost all expressions of Uighur Islamic faith as signs of potential religious extremism and ethnic separatism. At the detention centre, Alim was deprived of sleep and food, and subjected to hours of interrogation and verbal abuse. Other detainees report being placed in stress positions, tortured with electric shocks, and kept in isolation for long periods. When he wasn’t being interrogated, Alim was kept in a tiny cell with 20 other Uighur men.

…

China’s version of the “war on terror” depends less on drones and strikes by elite military units than facial recognition software and machine learning algorithms. Its targets are not foreigners but domestic minority populations who appear to threaten the Chinese Communist party’s authoritarian rule. In Xinjiang, the web of surveillance reaches from cameras on buildings, to the chips inside mobile devices, to Uighurs’ very physiognomy. Face scanners and biometric checkpoints track their movements almost everywhere.

…

Many Muslims who passed their first assessment were subsequently detained because someone else named them as “unsafe”. In thousands of cases, years of WeChat history was used as evidence of the need for Uighur suspects to be “transformed”. The state also assigned an additional 1.1 million Han and Uighur “big brothers and sisters” to conduct week-long assessments on Uighur families as uninvited guests in Uighur homes. Over the course of these stays, the relatives tested the “safe” qualities of those Uighurs who remained outside of the camp system by forcing them to participate in activities forbidden by certain forms of Islamic piety, such as drinking, smoking and dancing. They looked for any sign of resentment or any lack of enthusiasm in Chinese patriotic activities. They gave the children candy so that they would tell them the truth about what their parents thought.

…

The new security system has hollowed out Uighur communities. The government officials, civil servants and tech workers who have come to build, implement and monitor the system don’t seem to perceive Uighurs’ humanity. The only kind of Uighur life that can be recognised by the state is the one that the computer sees. This makes Uighurs like Dawut feel as though their lives only matter as data – code on a screen, numbers in camps. They have adapted their behaviour, and slowly even their thoughts, to the system.

“Uighurs are alive, but their entire lives are behind walls,” Dawut said softly. “It is like they are ghosts living in another world.”